Pastoring in a Secular Age

There is a series of virtually interchangeable terms floating around right now, each one making an effort to describe the cultural situation we find ourselves in: secularism, post-modernity, late-modernity, post-Christian. There are probably more. Each one is a shorthand-attempt to describe the changes in our world over the last century or so.

Some of what they describe is obvious. The world is quite clearly more suspicious of and hostile to religious ideas than it was in the past. Some is less obvious — like the ways modernity erodes Christianity from within, and the opportunities for ministry we’ll discover in this era.

In what follows, I want to sketch out four things about ministry in a post-Christian culture, ranging from the effects of modernity on the Church, to ways to think about evangelism, to why the Star Wars prequels sucked.

Modernity’s Impact On How We Read Scripture

Christianity itself has experienced erosion from within, as Christians embraced modernism and its methods of critiquing the text of scripture. Modernity gave birth to both liberalism and fundamentalism. Liberalism treats the Bible like any other ancient text, subject to the rational and historical criticism. It empowered liberals to demean the text, extracting only what could be justified “objectively” or — far worse — providing a façade of intellectual superiority to methods meant to extract from the Bible anything sacred, supernatural, or in some cases, morally demanding.

“Liberals drain the Scriptures of their mystery by taking on an authority over Scripture . . . Fundamentalists remove mystery via literalism.”

Fundamentalism arose as a reaction to liberalism, but make no mistake; it’s just as much a construct of modernity. In fundamentalism, the text remains absolutely sacred and absolutely true, and the Bible becomes known as the “literal Word of God.” In other words, the Bible gets treated like a scientific textbook, and literal interpretations of everything — including poems and prophecies — become necessary.

What both approaches share is intolerance for mystery. Modernism gave humanity a sense that everything was knowable — from the way the stars moved to the way life was created, right down to the origins of the universe. It created a built-in hubris and a confidence that we could know anything. This sense became part of the background of human thought, and is the underlying assumption of both liberalism and modernism. Liberals drain the Scriptures of their mystery by taking on an authority over Scripture, using an exacto knife to remove anything inconvenient or unverifiable via scientific inquiry. Fundamentalists remove mystery via literalism, and thus the “behemoth” in Job is obviously a dinosaur, or — as in the case of the book of Revelation — mystery is resolved with crude, two-dimensional allegorical interpretations, in which this mythic creature is ‘obviously’ that historical figure. (I’m reminded of 30 Rock’s Kenneth Parcel who once said, “My favorite subject in school was Science, where we studied the Old Testament.”)

What’s important to note is that liberalism and fundamentalism are more than just ideas or movements; they are impulses, shaped by a common cultural background. It’s not enough to make counterarguments (plenty of these exist, and the whole evangelical movement was intended to be a healthy reaction to both liberalism and fundamentalism); we have to understand that they’re less like a belief and more like a gravitational pull. We default towards skepticism or rigid literalism.

I think we’re living at a time where these impulses remain strong, but find themselves in tension with a growing reactionary impulse. This new strain is suspicious of both camps because it’s suspicious of certainty. Where Christians in the past had to do battle with angry atheists armed with intensely rational arguments, we’re increasingly encountering people whose posture is apathy and malaise. There’s still a broad sense of spiritual discontentment in the world, but rather than seeking to resolve that discontentment by getting questions answered, they’re looking for resolution in their experiences and in their relationships. So rather than try to make a case for the truth of Scripture, our challenge might be to make the case for the beauty of Scripture and the beauty of the biblical account for the world.

“The most convincing demonstrations of truth… are the saints and the beauty that the faith has generated.”

— Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI was probably the most skilled theologian to ever serve as a pope. He was German, rational, and a lover of rigorous scholarship. Even so, he saw that in a culture where the concept of truth was so eroded, the church had to shift its strategy to reach the lost. So if truth won’t capture hearts, goodness and beauty might. As he put it, “The most convincing demonstrations of truth… are the saints and the beauty that the faith has generated.”

Holding out the beauty and mystery of the biblical story — making an effort to capture imaginations and hearts — will bear more fruit than rational defenses of the canon, as important as those are. Likewise, communities of deep relationships, deep discipleship, and deep wisdom will attract unbelievers who look for meaning in their experiences more than in their rational beliefs.

Where the modern impulse is “rationalize, then believe,” the late-modern impulse is “believe, then rationalize.”

The Meaning of “Secularism”

It’s important to note that when the word “secularism” gets employed, it doesn’t necessarily mean pure, godless, secularism. Instead, it means that the cultural background of our lives isn’t defined by religion, and it means that religious affiliations are less firm and more fluid.

For instance, if you were born into a Roman Catholic family 500 years ago, it would have cost you greatly to leave the church. You’d be a pariah to your family, and probably to your whole town or village. Culturally, those ties were enormously strong. The same goes for almost any religious affiliation.

Today, things are fluid. You might be born into an Evangelical family, sent to Catholic schools, and as an adult, be a practicing Buddhist, and most people won’t blink an eye. True, your grandmother might gossip in disapproval, but it likely won’t sever the connections you have to family and community.

Disenchantment and the Star Wars Sequels

Recently, I had the chance to re-watch an original 1977 cut of Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. It is remarkable how much different that movie appears after seeing almost two decades worth of revisions, additional effects, and of course, the awful prequels. What made the original so good? What drew people (like me) in and turned them into geeks for 35 years? And likewise, what made the prequels so horrific?

It isn’t lack of action. The prequels are packed with lightsaber duels, dogfights in space, and pod races. It isn’t just that Jar Jar Binks was one of the worst ideas in movie history. And it isn’t just that the dialogue was more wooden than a lumberyard. “Cult” movies and their sequels have survived far worse. There was something else lost in the prequels; a charm, a mystery.

One can begin to see this even in the gap between the 1977 edition of A New Hope and the subsequent revisions. Starting in the 1990’s, Lucas began taking advantage of new technology to “update” the film with additional CGI animation, cleaning up certain effects, and adding a scene with Boba Fett.

By the time the prequels come around, the technology of special effects had developed so much as to make everything possible. The scenes became digitally dazzling, and everything, it seems, got dialed up to 11: creatures became more fantastical, lightsaber duels became more acrobatic, space fights and starships became more elaborate. It was, technologically speaking, everything all the time. If the original Trilogy was Led Zepplin, the prequels were Spinal Tap.

In all the elaboration, in the detail, in the shine and shimmer of digital effects, something vital was lost. There was an air of mystery in the original Trilogy, a sense of something unknown. Even the primitive special effects served this purpose, leaving space for the imagination to fill in the gaps.

“If the original Trilogy was Led Zepplin, the prequels were Spinal Tap.”

And then there were the midi-chlorians.

Perhaps nothing else in Star Wars history managed to erode the mystery than the addition of midi-chlorians to Episode I. If you’ve forgotten them, they come into the story when Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan meet young Anakin and test his midi-chlorian count. We come to find out that these are a life-form that lives inside of humans symbiotically, and in high enough numbers, they allow the person to use the force. Jedi aren’t “gifted,” so to speak, and the phrase “The force is strong with this one” is rendered meaningless; Jedi are infected with a microbe that allows them to do their thing. Goodbye enchantment.

Now, why go on this long tangent? Because I actually think it illustrates something the philosopher Charles Taylor describes in his seminal work, A Secular Age. The concept is called “disenchantement.” As Taylor sees it, the pre-modern world was “enchanted,” which meant that people had a sense that there was more to the world than they might see. They were vulnerable to spirits, to blessings and curses, to the will of God and to unknown spiritual forces in the world. There was a sense that the world had a purpose and a trajectory, that we lived in a “cosmos” — an ordered creation overseen by a divine person. Modernism “disenchanted” the world.

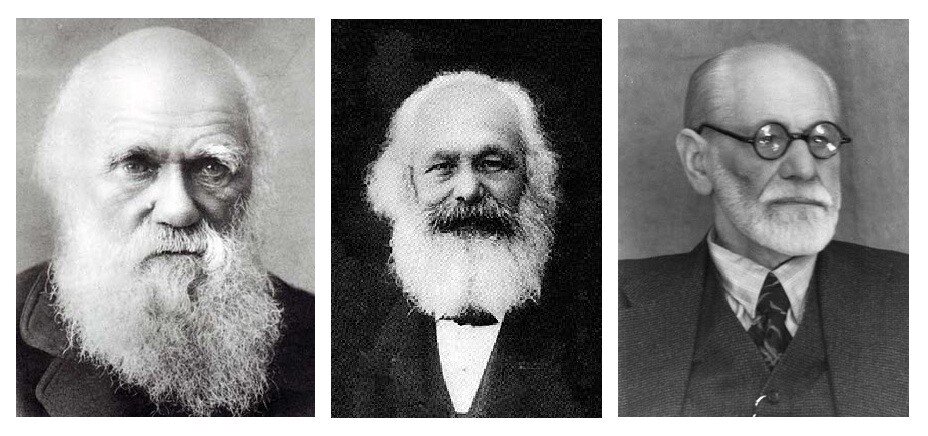

Darwin said we didn’t come from God, we came from monkeys. Marx said the most important thing in the world wasn’t transcendence, it was economics. Freud said the voice in your head wasn’t a demon, it was just your mother. The world became framed by immanence. Everything was knowable. Comprehensible.

The original Star Wars Trilogy, in all the ways it left questions open and invited imagination, in the way it used effects in a sparing way, was enchanted. It was an open world, with questions to explore and a sense of the unknown. The prequels, then, made the mistake of disenchanting the world. The mysteries all had answers. Even the overwhelming presence of CGI has a “secular age” parallel: the overwhelming culture of production and consumption. When every moment is a visual feast, nothing becomes worth celebrating. It was just too much. Like so many others, I left the theaters with a sense of malaise, wondering, “Is that all there is? Is that what we’ve been looking forward to for almost two decades?”

“The prequels made the mistake of disenchanting the world.”

And while the whole series is a product of a secular age (the concept of the Force has many parallels to a deistic, “human flourishing” theology that Taylor outlines), the gap between the two installments of the series seems to illustrate something that is lost between a world where the transcendent is possible and mystery hangs in the air, and a world where it isn’t — where rational, materialist explanations exist for everything.

In James K.A. Smith’s excellent introduction to Taylor’s work, we’re encouraged to notice the elephant in the room: that modernism’s disenchantment of the world hasn’t left it a better place. We’re encouraged not to cede any ground in the debate, too, to take courage in knowing that the disenchanted take on the world is just that: a take. A perspective. A constructed world. And given the evidence of a broadly felt spiritual malaise, perhaps it’s worth taking a hammer to a few of the stones at its foundation.

Wisdom-Seeking and Practices

There’s been a rise in what I’m going to call Wisdom-Seeking. People are looking for a way of life that works, and they’re less interested in why it works.

So for instance, Brene Brown’s work on vulnerability has gotten tremendous traction because it describes an approach to relationships that works. Tim Ferriss, a self-help guru, has a massive audience because of his endless quest for “lifehacks” — practices around diet, exercise, work habits, relationships, and sex that are effective. Ferriss has one of the most popular podcasts in the world and has written multiple New York Times-bestselling books. Brown also has written bestsellers, and has one of the most-viewed TED talks of all time on YouTube.

Though Brown is a Christian and Ferriss is not, their work is a-theological. God, the transcendent, and the supernatural don’t enter into it. And they’re not alone. You could fill a page with lists of self-help gurus and quasi-religious movements that are promising people the good life: Paleo eating, veganism, Soul Cycle, Crossfit, Yoga, Pilates, Mindfulness Meditation. What matters is practice: do these methods work at improving my life or do they not?

Here, I think the opportunity for the church is in advocating for a uniquely Christian way of life. Can we point to our churches as places that foster life-giving, Christ-centered, life-shaping practices that actually improve lives? I think in many cases we can’t and the answer can be found above.

In the years to come, the church would do well to become deeply acquainted with the Bible’s wisdom literature and the wealth of resources that come from church history on spiritual formation. We need to be a people who embody wise living and foster it in homes and relationships through rhythms of worship, prayer, feasting and fasting. We need a way of life that is notably different than the world around us — not with a sense of moral superiority, but with a sense that our lives are oriented around a different set of priorities and values. Wisdom will prove itself right, bearing fruit in the lives of those who seek it.

“If we honored the table and practiced feasting and fasting the way Christians (and Jews) have honored the table throughout history, we’d build a countercultural movement.”

If we honored the table and practiced feasting and fasting the way Christians (and Jews) have honored the table throughout history, we’d build a countercultural movement. We have a wealth of resources for contemplative spirituality that offer far more than any meditation retreat ever could, and if the word “contemplative” makes the Reformed part of you nervous, go read the Puritans again. Their understanding of prayer, meditation, and the contemplative life was far more mysterious and wonderful than our own.

The point being: we have an inheritance as the people of God that could provide the foundation to a wisdom-filled, Christ-centered way of life in the world. Our churches crave it. Our own souls crave it. And if we invest ourselves in it, we’ll be able to bear witness in profound ways to a world that craves it too.

Mike Cosper lives in Louisville, Kentucky. He is the author of Faith Among the Faithless: Learning from Esther How to Live in a World Gone Mad (Thomas Nelson, 2018), Recapturing the Wonder: Transcendent Faith in a Disenchanted World (IVP Books, 2017), The Stories We Tell: How TV and Movies Long for and Echo the Truth (Crossway, 2014), and Rhythms of Grace: How the Church’s Worship Tells the Story of the Gospel (Crossway, 2013). You can follow him on Twitter.